The collision repair business uses a lot of energy one way or another, and while many bodyshops have done as much as possible to reduce electricity / gas consumption, some of the ‘energy’ is buried in the new parts used in the repair as well as the refinishing system products. In turn, those suppliers are doing things to reduce the amount of energy used.

Regardless of belief, this is the relentless drive for efficiency.

In turn this is related directly to the residual value of the vehicle, where the lower it falls the point at which it simply goes to salvage auction without any input from a VDA becomes more likely. Right now we have new vehicle price inflation directly from the infamous lockdown years, where many manufacturers realised they could make more profit from fewer vehicle builds. In addition, the long march to electrification which was supposed to encompass all forms of powertrain, quickly became politicised and driven towards the most expensive and least profitable version, BEV.

Add into this mix catastrophic BEV residual value falls (I think this is a painful blip which should correct) and we can see the base cost of the parts has been driven upwards while the available value of the vehicle to be repaired has been driven downwards.

Progress and history

The hallmark of the present industrialised society is still a mantra that it’s easier to buy a new item than get a damaged item repaired. For collision repairers of course we do not support the idea, replacing only the items in the repair process that are not possible to refurbish (seat belts, airbags, SRS sensors, single use screws / bolts, certain UHS steel alloy panels and so on).

Being able to strip something apart and put it back together relies on skill, manufacturer repair process information, and equipment. Taking care to understand how something is put together and so understand how it can come apart is retained knowledge in the bodyshop. This is valuable to the business, and yet inevitably when a person leaves, that knowledge leaves too.

It is essential for business continuity that retention of the knowledge but giving staff the freedom to leave for what ever reason is achieved. To do this from the 20th century view required an apprenticeship, where more knowledgeable staff would transfer information to newer team members. This can be achieved even without formal apprenticeships.

However, there are headwinds here as well.

At the start of the internet and World Wide Wwb, there was a body of printed works and one could research between both sources. Due to cost of storage – even though this has fallen in unit terms – the growth of archive exceeds cost reduction rate. So, especially with corporate and media sites, most of the information is ‘gone’ in under 5 years.

The point: Not only is the information gone, but the knowledge behind that is ‘retired’ or moves to another occupation. So, a net loss of intellect.

To research any subject from scratch means using electronic records mainly reside on things like blogs and ‘Wayback machine’. The risk is the material may have errors, but this getting more difficult to verify.

Why is this important?

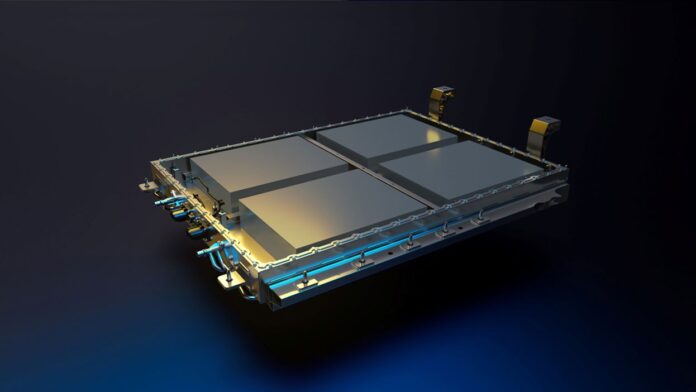

Batteries ahoy!

The main reason BEVs have taken such a residual value hit is because apart from market resistance (a completely usual feature of technology mass adoption) and issues over access to electricity, insurers are very nervous.

The first real mass market BEV was the Nissan Leaf in 2010, which as we now know made the error of inadequately cooling the battery, and in some markets, failing to provide battery heating, which caused legendary loss of energy retention. Within the life-cycle of the first generation Leaf the thermal management issue was completely fixed, the battery chemistry revised several times, the energy storage capacity and the range were increased significantly.

Legends can be created relatively quickly, and remain long, long after the material reality has changed.

Catastrophic battery failures have continued from the start until now, but catastrophic loss of storage capacity has almost vanished – apart from those users who think using rapid charging routinely is a good idea – which means with care an HV Li-Ion battery pack is likely to have a service life of 10 or more years. The data is still coming in, and the knowledge growing.

I would hope most insurers are reassured about battery degradation – the equivalent of a collision repair arriving with an internal combustion engine within minutes of total failure. That’s why VDAs and repairers in general ned to evaluate HV Li-Ion battery health as part of the initial process.

So, what’s left? Well, great difficulty in understanding what has happened to the HV Li-Ion battery during the impact. Right now, due to the overall lack of understanding, a damaged battery is a major cost (removal, storage, if information is available – analysis, repair or possible toxic waste disposal). The situation is evolving, but right now repair of a battery is a risky process that could lead to total loss.

The alternative is a new HV battery pack, which if the BEV is more than a few years old, instantly puts the vehicle into salvage.

Because the salvage by hook or crook does get to be repaired, there is growing evidence the present approach to battery damage assessment is over cautious. There’s the key. Growing evidence. Data.

A brighter side

The large HV Li-Ion battery is already a feature of our bodyshop world, and even if all new BEV sales stopped immediately, the present parc means BEVs will turn up for assessment or repair for many years to come. The economics around HV Li-Ion battery repair will change, which requires a source of information to do that, the required equipment and of course knowledge.

The BEV fleet is unlikely to achieve more than 30 per cent overall penetration by 2030, but there is plenty of business to be had and a chance to be involved in the evolution from the present possibly over cautious approach to valuation and a better outcome for all.